When you look at Impressionist paintings, with their bright tones, broad brushstrokes, and scenes of leisure, you probably don't think of them being very "radical."

Consider these three paintings.

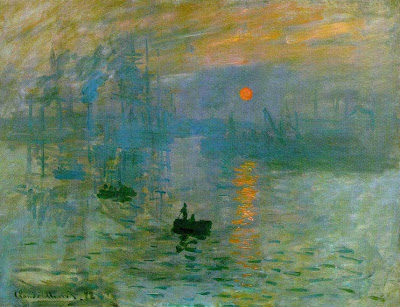

Claude Monet, Impression Sunrise.

Edouard Manet, Olympia.*

* (While Manet is not technically an Impressionist painter, his loose brushstroke and innovative subject matter made him one of the greatest influences of Impressionism.)

* (While Manet is not technically an Impressionist painter, his loose brushstroke and innovative subject matter made him one of the greatest influences of Impressionism.)All three of paintings above are examples of art that much of the French public found horrifying when they were first shown. Art critic Louis Leroy, after looking at Monet's Impression Sunrise, mockingly referred to the painters of this new, loose, radical style "Impressionists," which is where the term originates.

The French public and art critics detested Impressionism for many reasons. First and foremost, it simply wasn't considered tasteful. The highest regard was given to history and religious paintings, which could be viewed at the annual Salon.

The Salon, or "Exhibition of Living Artists," was basically an art show that allowed artists to show their work to the public. Getting work accepted in the Salon helped them obtain commissions, sell their works, and many times in the 1800s helped revitalize France's war-torn image. The cost was one franc, a fairly low price for most Parisians, and each show usually lasted a few months. Some Salons drew as many as a million visitors.

In order to be accepted into the Salon, the submitted artwork had to be reviewed by a jury. The jury often consisted of members of the French Royal Academy, who preferred the "academic style" of painting and, as was stated previously, history and religious paintings. Darlings of the Academy that were accepted time and again into the Salons included artists like William-Adolphe Bouguereau, Jean-Leon Gerome, and Alexandre Canabel.

William-Adolphe Bouguereau, Fardeau Agreable.

Jean-Leon Gerome, Un Combat de Coqs.

Precise lines, intense naturalism, and a love for mythological themes defined the academic style in the 1800s. That is part of the reason why the Salon jury rejected the Impressionists' work so frequently. That isn't to say that all the Impressionists experienced rejection - Degas and Morisot had quite a few works that were accepted. It was the jury's inconsistency, though, that infuriated them.

In 1863, a number of artists and Parisians were speaking out against the unfair policies of the Salons and the fact that so many artists were being rejected. Napoleon III intervened and decided that there should be a Salon for the rejected works - the Salon des Refuses. Poorly organized and poorly funded, the show was a joke to most of the public. Much of the ridicule was given to Manet's Olympia. Never before had a nude model been presented this way, with such a forward position and a cold stare. It was one of the first painted nudes that seemed to hold her own - an idea that was not appreciated in the mid to late 1800s.

Critics were so taken aback by the black cat in the painting, which was interpreted to represent the model's sexuality, that it became a symbol for Manet in satirical cartoons.

In my paper I also explained how the first Impressionist exhibit was influenced by the Salon of 1866 and the Universal Exposition, but I will not delve into these events for the purpose of keeping this post short. Throughout both events, the jury continued to reject a large number of submissions. Out of the 3,000 pieces that were submitted to the Salon of 1867 (which combined with the Universal Exposition), 2,000 were rejected.

In my paper I also explained how the first Impressionist exhibit was influenced by the Salon of 1866 and the Universal Exposition, but I will not delve into these events for the purpose of keeping this post short. Throughout both events, the jury continued to reject a large number of submissions. Out of the 3,000 pieces that were submitted to the Salon of 1867 (which combined with the Universal Exposition), 2,000 were rejected.It was around this time that Bazille, Monet, and the rest of the Impressionists began to throw around the idea of creating their own society. The idea came to realization in 1873 with the creation of the Société anonyme des artistes peintres, scupteurs, graveurs, etc. They decided to open their own exhibition in direct retaliation against the Salon.

So on April 15, 1874, the first Impressionist exhibition opened on the Boulevard de Capucines at photographer Nadar's famous studio.

Out of the 30 artists that presented work at the exhibition, less than half were Impressionist painters (and incidentally, most of their reputations were lost in obscurity after the show). Neverthless, the Impressionists were the stars of the show: Monet, Renoir, Morisot, Degas, Cézanne, Pissarro, and Sisley all presented works that were viewed quite positively.

Out of the 30 artists that presented work at the exhibition, less than half were Impressionist painters (and incidentally, most of their reputations were lost in obscurity after the show). Neverthless, the Impressionists were the stars of the show: Monet, Renoir, Morisot, Degas, Cézanne, Pissarro, and Sisley all presented works that were viewed quite positively.Seven more exhibitions followed the one in 1874, but around 1889, Impressionism met its end. Still, the first exhibition garnered the Impressionists the attention and respect they deserved but could not obtain through a Salon.

Working on this project gave me a new appreciation for the Impressionists and their paintings. It's so interesting to think that they put so much hard work, effort, and time into getting their new style of painting accepted by other people. Today it's hard to imagine a person who doesn't admire the Impressionist paintings.

No comments:

Post a Comment